How will markets be affected?

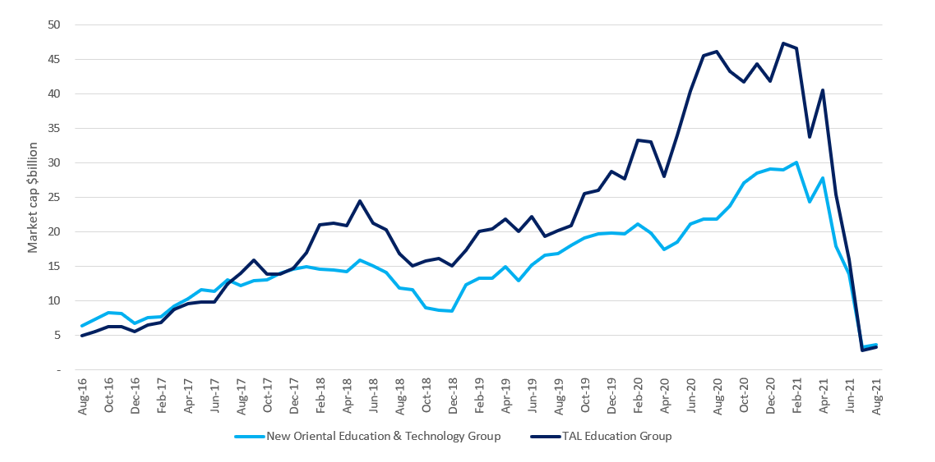

We must not forget, however, that China is the second largest economy in the world and growth opportunities remain, even as the economic regime evolves. Some of our portfolio companies, which are listed elsewhere, have significant exposure to China and we remain optimistic about their growth prospects, especially where revenues are aligned to new policy objectives. For example, China’s plans to decarbonise will be a likely boon for electric vehicle manufacturers, and in turn as a supplier our holding TE Connectivity, which derives a fifth of its revenues from the country. Similarly, the flip side of the government’s ban on after-school tutoring has been the announcement of new policies to promote greater participation in sports, which should benefit another of our holdings, Adidas, for which China accounts for a quarter of sales.